Explainable AI - Building Trust at the Clinician-Machine Interface

“Show your work.” Many of us may remember (some more fondly than others) this rule from mathematics exams. Why was this such a strict requirement? In order to appropriately give credit to a student, teachers need to trust that the student knows how to approach a problem and reason through the necessary steps to arrive at the correct answer. Trust is at the center of healthy relationships, including patient-clinician and clinician-machine ones.

Successful implementation of artificial intelligence (AI) in healthcare poses major challenges that extend far beyond the difficulty of processing unstructured healthcare data, for example. If trust is not at the foundation of the clinician-machine relationship, useful AI algorithms will not see the light of day. How might healthcare AI teams best construct this necessary trust?

Often termed a “black box”, the inner-workings of commonly used AI algorithms, such as neural networks, are murky. Many features of a dataset can be used as inputs (e.g. weight, medication list, and zip code), and data scientists typically manipulate, augment, and create novel features from these inputs so that an algorithm can ingest a greater number of and more complex relationships among data. With great complexity comes great predictions, potentially—but poor explainability, or the ability of the algorithm to explain how and why it arrived at the prediction that it did.

Strategies for Explaining AI

How might one improve explainability and lighten the black box of their model? According to IBM, there are three main approaches of delivering more explainable AI (XAI) systems: 1) simulation-based prediction accuracy explanations; 2) traceability (how individual neurons of a neural network depend on each other, for example); 3) suspending people’s distrust of AI, providing clear descriptions of each step of AI processes. In fact, to accommodate building XAI, IBM has published open source code for demoing various XAI techniques.

Myriads of specific explainability techniques fall under different categories, such as text explanations and feature relevance (Table 1) and are currently being tested and updated to produce quality XAI for different types of models. An example of a simple, text explanation technique is decision tree (DT) decomposition. This is performed by “walking” through a DT model from “root node” to “leaf nodes” (more on DTs here and here) and generating text that highlights which features of the query were used by the DT to produce the prediction. For example:

Patient A is considered moderate-to-high risk for readmission within 30 days because they:

are >65 years old;have had consistent, difficult-to-control congestive heart failure for >2 years;are taking >5 cardiovascular medications; andhave missed >25% of their outpatient follow-up appointments

From this we can see that decision trees are innately explainable. Great! Why not use decision trees for all of our tasks and receive explainable results? Caveats to DTs include their high reactivity and instability—namely, the ability for insignificant changes in the input data to cause large variations in the predictions—as well as their failure to deal with linear variable-outcome relationships and an exponential increase in complexity with each increase in “leaf” level. Christoph Molnar goes into more depth on this topic in Interpretable Machine Learning.

Table 1: Various post-hoc methodologies by which to explain AI processes and predictions. For more info on dimensionality reduction, see here.

Game Theory & Activation Mapping

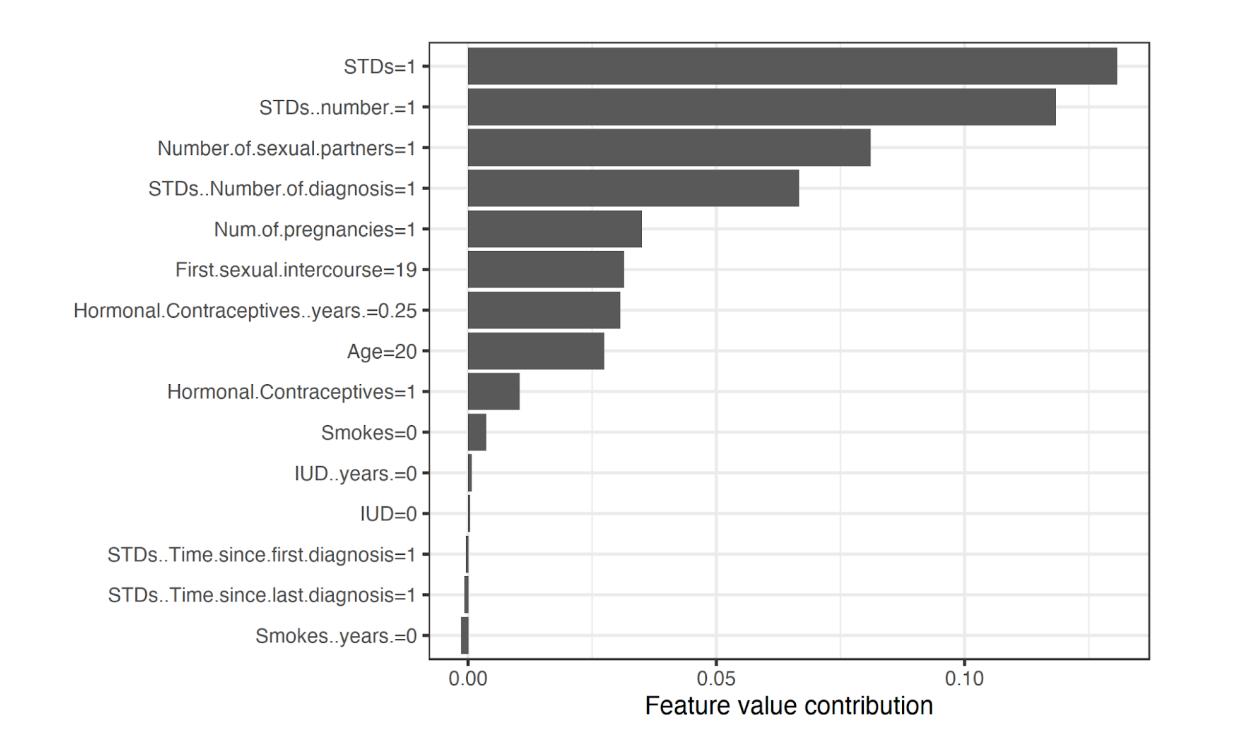

A more complex technique borrowed from game theory is a feature relevance approach that computes Shapley values, which describe the relative importance of each model feature on the output prediction. Figure 1 shows Shapley values from a random forest model that predicts cervical cancer risk trained on a University of California, Irvine Machine Learning Repository dataset. According to this analysis, features such as the number of diagnosed STDs and number of sexual partners appeared to increase cervical cancer risk the most (i.e. greater feature value contribution). This technique is model-agnostic as Shapley values do not rely on the nature of the model that it is attempting to explain, a noteworthy goal for all XAI techniques.

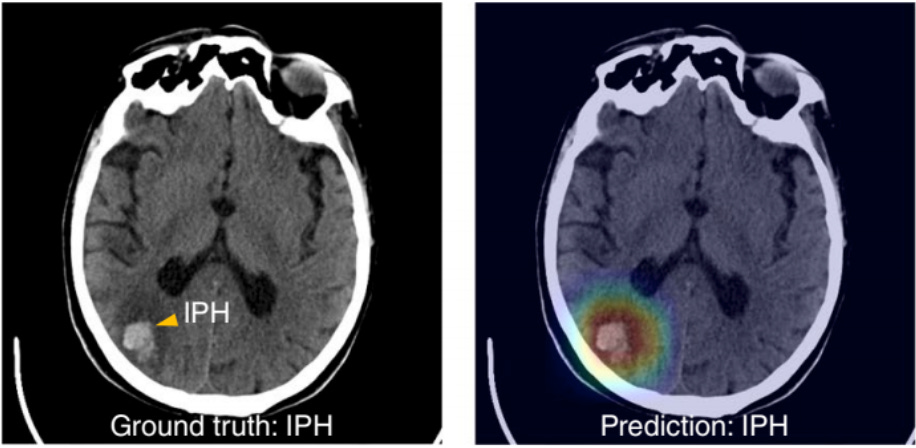

XAI can be applied to computer vision predictions as well. Figure 2 shows how a deep learning model has correctly predicted a patient to have intraparenchymal hemorrhage (IPH), or bleeding within the functional tissue of the brain (Lee, et al.). Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) was then used to produce an overlaid heat map to identify which aspects of the image were relevant for making this prediction of IPH, with the color red signifying greater relevance.

Increased Importance of Explainability in Healthcare Venues

However, is it integral to trace the processes and “work” of an AI system? Some machine learning experts argue that AI models don’t need to be understood—as long as the outputting model has demonstrated favorable statistics during testing, the output can be trusted.

While AI that predicts promising customer segments or stock selections may not need to provide explicit reasoning for its outputs, healthcare data extensively relies on traceable decision-making. This is incredibly important when understanding not only the patient one is treating, but the specific population to which this patient belongs. Say a model predicting readmission rate is 99% accurate and has high precision and recall—but only when dealing with patients who are: over 65 years old, smokers, from Montana, and affected by peripheral artery disease. Apply that model to patients in a Mumbai hospital unit and prediction quality may plummet. XAI outputs not only help end users understand how the model is “thinking,” but can potentially be useful for assessing bias as well as data leakage. When scaling AI models, it can be argued that understanding the fine details of the raw dataset may be more important than understanding the weights and relationships between variables of a trained model.

Still, certain applications of AI within healthcare systems may require explainability. Models that are action-oriented and trained to suggest/order imaging or lab studies are perfect examples. In order to place an order, one usually has to provide at least a phrase of why the patient requires the investigation of interest. If the model cannot provide this, then will it provide significant clinical value? A well-trained XAI would deliver the reasoning needed to qualify the order.

Decisions whose nuances can make the difference between life and death should have clear, reviewed, and vetted reasoning behind them. If AI models are to be valuable intraoperatively, within ICUs, inside ambulances, or within other high-stakes healthcare venues, then ultra-transparency of how the AI arrived at a solution or piece of information is critical.

Furthermore, a model may be explainable but are the explanations relevant? Let’s say a model is trained to select antibiotics and their dosages for patients in the ICU, and it chooses vancomycin 500 mg IV every 6 hours at a rate of 8mg/min for a patient with sepsis. Below that prediction the model explains that this was chosen because the patient received this dose and rate the last time that they were in the ICU. That is quite unhelpful reasoning, and a clinician would unlikely find that reasoning sound. What the model may have incorporated but not revealed is that the patient lost a significant amount of weight and developed kidney dysfunction in between the two ICU visits. They now distribute throughout and clear from their body the vancomycin much differently, which is critical to know before treating this patient.

Towards a Responsible, Explainable, Patient-Centric AI Standard

At the end of the day, the overarching goal of XAI should be to develop model-agnostic, responsible AI, which can be described as “a methodology for the large-scale implementation of AI methods in real organizations with fairness, model explainability and accountability at its core” that works regardless of the specific model of interest (Arrieta, et al). Leaders from Precise4q, a stroke prediction consortium, outline additional clinical responsibilities for XAI beyond data-driven explanations. Aspects such as informed consent, approval for use as medical devices, liability, and shared decision-making need to be teased out before any AI system is deployed in a clinical setting. Additionally, they stress that AI should uphold the core ethical values of medicine: autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice (Amann, et al).

Proper healthcare is patient-centric. Providers are trusted to have the best interest of the patient at heart. Similarly, XAI needs to evolve such that providers trust its predictions to a similar degree—perhaps a bit more than a teacher trusts their students’ work on a math exam.