Drifting Away — MLOps in Clinical AI

Intro to monitoring for data drift, concept drift, feature skew, and more

Change is inevitable. It would be unwise to plan for only one rainy day. Alternatively, it would be wise to have a dynamic plan in place that outlines procedures for how to best cope with and adapt to the rainy days when they do arrive. Whether talking about literal precipitation, financial stability, or the anticipation of novel input data to a clinical machine learning (ML) model, the same wisdom applies.

It is no walk in the park to design and execute an end-to-end clinical ML environment. One needs to: scope the goals of stakeholders to identify a project’s goal; identify which data matches that goal; get permission to access the data; curate, assess, describe the data; preprocess the data; build a model; and validate the model, to name a few of the myriad of important tasks one needs to consider.

Let’s say one surmounts all of the difficulties that come with executing a clinical ML model. Great! Performance is high. Stakeholders are happy. Value is seemingly added to the clinic as a whole. Everything seems great. Lurking in the ether, however, an insidious mastermind whom we’ve met already is adrift, interfering with all that seemed great with our new model. Change. Our clinical input data slowly changes, drifts, morphs into a slightly different animal.

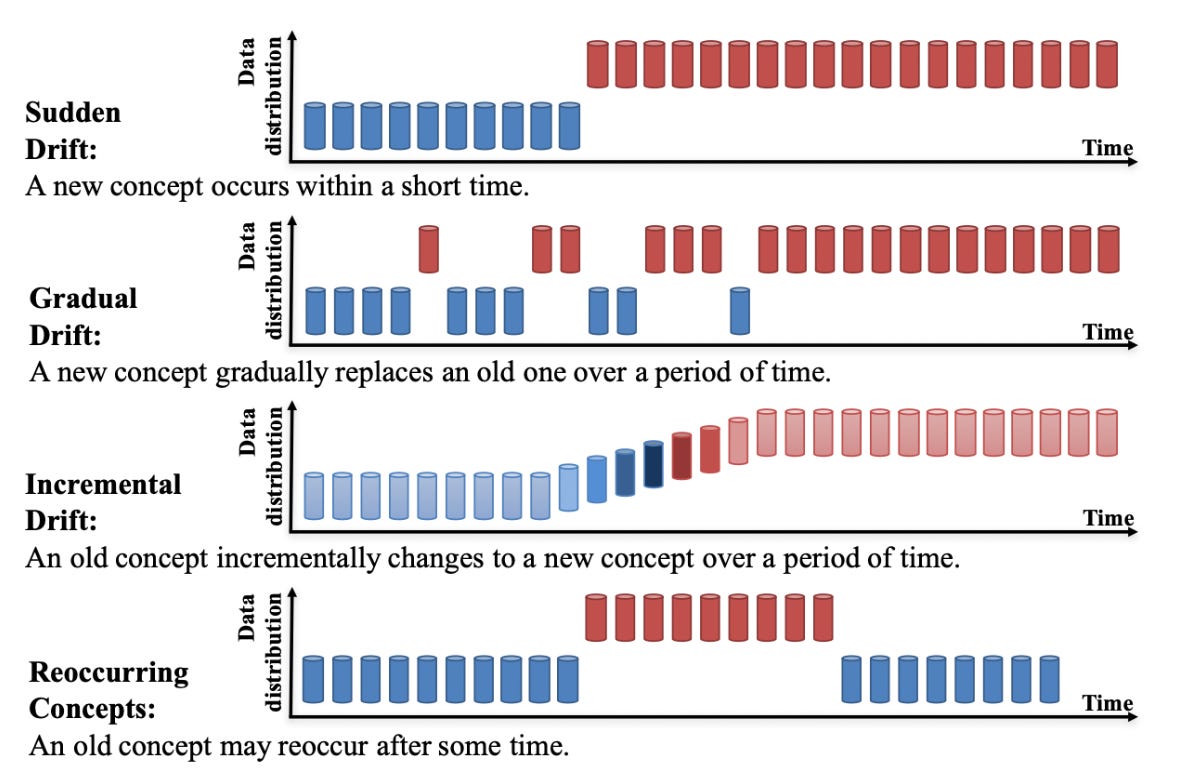

Depending on the use case, such data drift and concept drift (changes of the relationships between inputs and outputs, i.e. between the data and labels) of the data could decimate performance of models and lead to inaccurate predictions, potentially causing suboptimal care for patients. Data drift is just one of many issues related to the post-integration phase of clinical AI. Thus, proper maintenance and continual reassessment of deployed models is imperative to effectively cope with data drift.

What does all of this mean? Drifting input data causes our model that was carefully crafted to behave and output predictions for a certain use case to now see data that is different from the data on which it was trained—likely degrading the performance of the model over time. A potentially useful example to highlight the importance of monitoring and adapting to this drift is a physician’s continuing medical education (CME). What if a physician graduated from a medical school, residency, and/or fellowship program and started practicing but never reviewed any new literature, attended CME courses, went to conferences, or studied for (required) re-examinations pertaining to their board license. Well, they would not be up-to-date with (sometimes swift) changes in the medical field, such as regulation changes, updated treatment guidelines, and new pharmaceuticals, that have surfaced since they graduated. Quality patient care would be lacking. Clinical ML models must also be committed to a life-long learning and relearning regimen.

Examples in which this continual maintenance, or post-integration surveillance, becomes imperative include: the change of the indicated use of a medication; the drift in demographics of a given patient care geography; the shift in insurance coverage policies for a health system. However, one could argue it’s important to monitor for drift for virtually any model that is deployed. Automated tracking of drift built into a clinical ML pipeline would be an ideal scenario, and tools exist that can help configure such pipeline components. See more guidance from Google on data drift detection and feature skew monitoring.

How does one track or detect that these ML models are, well, adrift? Several useful analytical frameworks for monitoring ML drifts have utilized methods that span from statistical tests to drift-detection algorithms, some of which define a post-training dataset as the collective data that is introduced to the model after the initial training of the model. Some commonly used methods include the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (comparing cumulative distributions of training dataset and post-training set), the Population Stability Index (comparing distribution of target variable within the post-training dataset with that of the original training dataset), or the Adaptive Windowing Drift Detection algorithm (user-defined threshold to trigger drift warning of incoming data based on the mean). One could also train an additional model that differentiates between original training data and new, significantly different data—but this approach is relatively experimental.

Once drift is detected, a health system should respond and adapt. Retraining the ML model with a new dataset is an option. This may include shuffling the old training dataset, mixing some of the old training data with new training data, or taking a completely new data sample for training the model. Another option is to weight the training data based on how different it is from the current data sample pool. This may be an intricate process, depending on the speed of change of the data sample pool. Finally, incremental learning is another great technique for combating data/concept drift by constantly (or at specified time-points) retraining the model and redeploying it for use by clinicians so that the model is as up-to-date as it can be. In carrying out any of these approaches, beware of the caveats and difficulties. Two main ones include 1) the time and cost of constant retraining for incremental learning and 2) the regulatory and data-sharing aspects of retrieving new, different data for drift-proofing the model.

Importantly, certain kinds of drifts may not affect how well certain kinds of models perform over time or across populations. For example, if a model was trained to detect breast cancer from imaging data, then this type of biological data may not drift significantly over time. As Dr. Nigam Shah, Chief Data Scientist for Stanford Health Care, points out, “if a model is based on biology, then they need to be generalizable to convince me they are any good”. Here, generalizability broadly refers to the ability for a model to perform well across space, time, populations, datasets. However, Shah feels that models trained on data that are related to the “operational” aspects of healthcare, such as predicting the likelihood of emergency room readmissions or the need for hospital follow-up, should not be expected to generalize. In fact, it may be an alarm if those models do indeed generalize since these operational aspects of healthcare differ so greatly from country to country, even one health system to the next.